THE CIVILISING MISSION

문명화 사명

CUSTODIAN OF HUMAN CIVILISATION

Humanity stands at the precipice of collapse, ensnared by global turmoil and moral decay. An age marked by lawlessness, rampant materialism, widespread deceit, eroding principles, failing education systems, stifling political correctness, uninspired art and architecture, environmental devastation, and an unhealthy fixation on greed, violence, self-gratification, and ethical decline has taken root. Society unravels as respect for hierarchy is dismissed, merit is mocked, diligence is overlooked, families are abandoned, elders are disregarded, and division spreads unchecked, hastening civilisation’s decline.

Rising from this desolation, the Myeong Commonwealth emerges as the final stronghold of a once-vibrant Confucian civilisation, entrusted with preserving thousands of years of wisdom, culture, and virtue. In a world bereft of integrity and harmony, the Commonwealth shines as a guiding light, championing the restoration of moral clarity, the safeguarding of cherished traditions, and the cultivation of a just and principled society.

With unwavering commitment, the Myeong Commonwealth pledges to re-establish order, revive authentic artistic expression, promote integrity, restore reverence for the divine, elevate educational standards, challenge oppressive ideologies, uphold human dignity, strengthen family bonds, and deliver justice to those who betray trust.

Through time-honoured rituals, sacred traditions, and uplifting cultural practices, the Myeong Commonwealth strives to foster a society of exemplary character, where devotion to the Divine is central, the teachings of the Sages are earnestly followed, moral truths are steadfastly upheld, and the culture of despair is overcome. In this new era, divisive cancel culture is rejected, the balance between rights and responsibilities is restored, and the pursuit of wisdom and virtue lights the way through the gathering shadows of hopelessness.

THE RADIANCE OF CONFUCIAN CIVILISATION

In a world grappling with division, environmental crises, and uncertainty, the values of East Asian culture—rooted in the Confucian civilisations China, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam—radiate as a beacon of unity, resilience, and hope. Founded on principles of collective responsibility, effective leadership, and disciplined progress, this way of life offers practical solutions to today’s most pressing challenges. Unlike certain Western trends that prioritise individual rights and can exacerbate divisions, Confucian values focus on collaboration for the common good, providing a blueprint for a sustainable and prosperous future.

Unity and Togetherness

Central to Confucian culture is the conviction that society flourishes when individuals place harmony and collective well-being above personal interests. This fosters cohesive communities capable of addressing challenges collectively, resulting in lower mortality rates during epidemics, lower crime rates, and lower levels of corruption. By contrast, some contemporary Western trends, often termed 'woke culture', can overemphasise individual differences, such as debates over identity or historical grievances, leading to societal fractures. Confucian values, by promoting shared objectives, enable societies to remain united and prepared to tackle global issues like environmental degradation or resource scarcity.

Meritocracy for Long-Term Success

Confucian nations value leaders who are skilled, thoroughly trained, and future-focused. Leaders are selected through rigorous processes, enabling the country to plan strategically and achieve ambitions in the long run. These approaches avoid the short-termism prevalent in some modern Western democracies, where electoral cycles can lead to populist decisions that neglect long-term needs.

In certain Western nations, ideological debates—such as those over police funding or diversity policies—have caused confusion and unrest, with violent crime and acts of terrorism being increasingly rampant. Confucian statesmanship, which emphasises practical outcomes over emotive rhetoric, provides a more stable framework for addressing complex modern challenges.

Education and Diligence for a Robust Future

Confucian civilisation places immense value on education and hard work, equipping individuals for a rapidly evolving world, and producing some of the best experts in technology, artificial intelligence, and renewable energy for the twenty-first century. Conversely, the steadily 'progressive' Western education systems are facing challenges from disputes over curricula, such as removing classic literature or prioritising issues of 'racial justice' and 'gender fluidity' over core skills such as mathematics. Confucian systems, by rewarding effort and merit, create opportunities for all, ensuring societies remain competitive and resilient.

Protecting the Environment

Humanity’s survival depends on safeguarding the environment, and Confucian cultures are leading with practical, collective efforts. The emphasis on the Confucian doctrine of the mean reflects a commitment to balancing human needs with nature’s limits. In the modern Western world, environmental activism often focuses on protests or symbolic gestures rather than systemic change. Confucian cultures, with their emphasis on discipline and collective sacrifice, are better equipped to make the difficult decisions required to protect the planet.

A Resilient Sense of Identity, Not Self-Hate

Confucian societies harmonise tradition with modernity, maintaining strong cultural roots while achieving global success. South Korea’s K-pop and Japan’s anime captivate audiences worldwide, reflecting confidence in their cultural identity. This balance provides stability, helping people remain resilient during crises. In contrast, some Western societies grapple with debates over history or racial or gender identity, fostering disconnection. Confucian cultures, with their clear sense of purpose and tradition, offer a firmer foundation for enduring challenges.

A Way Forward

As humanity confronts threats like technological disruption and social division, Confucian civilisation provides a superior path forward. By prioritising unity, effective leadership, education, sustainability, and cultural pride, East Asian Confucian societies demonstrate how to build a future that is robust, equitable, and enduring. While Western trends like 'woke' culture seek to promote fairness, they can sometimes sow division and distraction. Confucian values, with their focus on collaboration and forward-thinking, offer a clearer route to a world where humanity can not only survive but thrive.

THE FOUR CIVILISING INSTRUMENTS

Classic Poetry

In the writings of old poets, one finds the ability to nurture virtues of meekness, tenderness, truthfulness, and integrity, all the while dispelling folly.

Classic History

In the annals of ancient history, there lies the capacity to foster a comprehensive grasp of the world and wisdom of bygone eras, purging deceit in the process.

Classic Rituals

Through the observance of traditional ceremonies, one can develop qualities of politeness, humility, reverence, and decorum, casting aside unnecessary distractions.

Classic Music

In the harmonies of classical melodies, there exists the potential to cultivate open-mindedness, magnanimity, simplicity, and benevolence, while banishing excess and opulence.

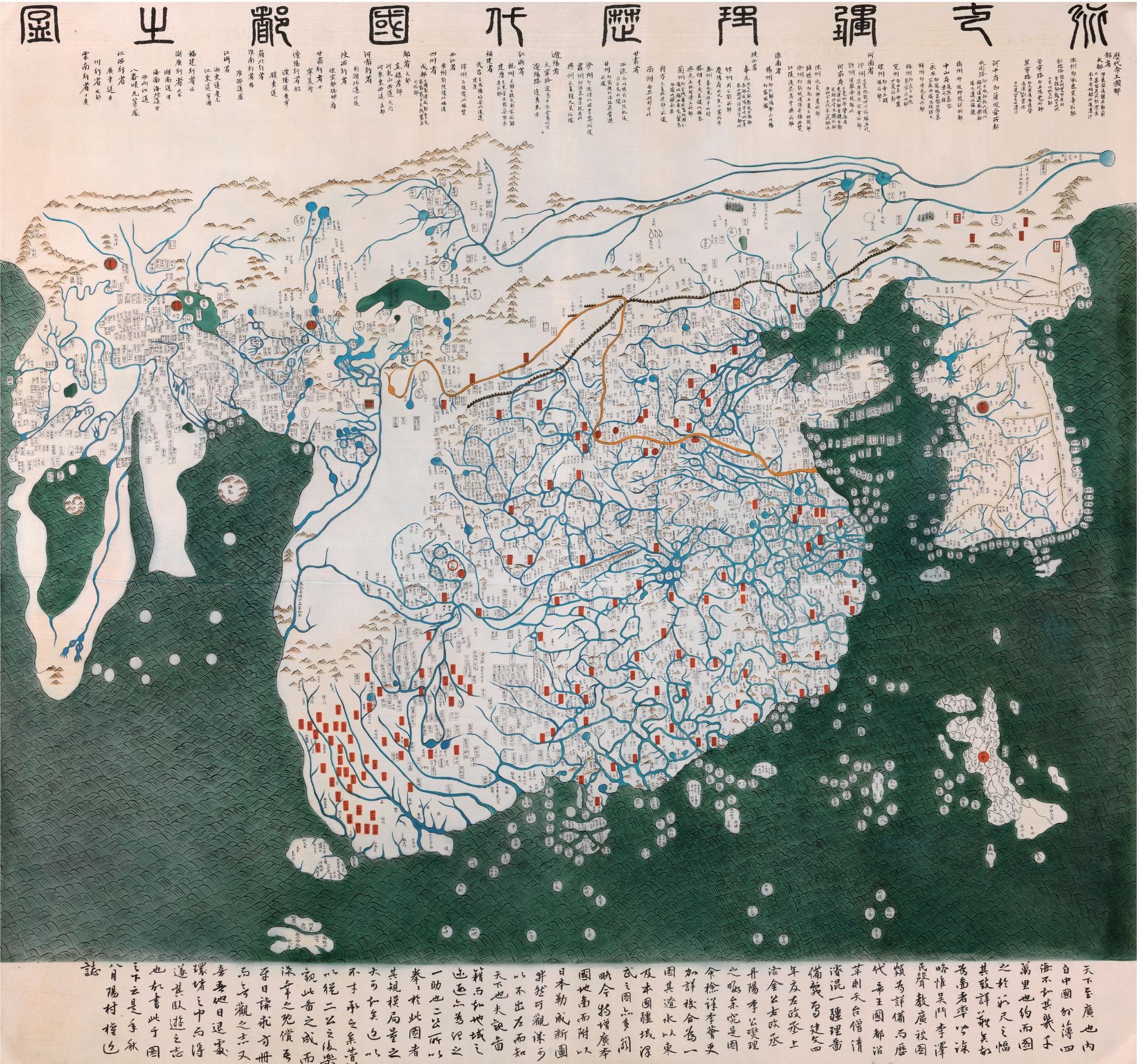

The era of the Ming (1368-1662), nestled between two periods of barbarous conquest, was not an age of darkness, as alleged by its critics. Conceived by the Hongmu Emperor (r. 1368-1398), The Ming Empire—the Commonwealth of Great Illumination—triumphantly dismantled the oppressive regime of Dai Ön ulus (1279-1368) by ousting uncivilised colonialists from the Celestial Realm, shattering the brutal grip of the once-mighty Mongol Empire across the Eurasian continent.

The Ming Empire ushered forth an era of Pax Minga, upholding its timeless vow to refrain from encroaching upon fifteen neighbouring realms; embracing commerce with distant dominions through the tributary system, within which the Empire graciously exchanged imperial treasures as tokens of goodwill. The Ming Emperor, designated as the Son of Heaven and entrusted with the Mandate of Heaven, presided over a Confucian commonwealth, within which a civilisation of humaneness and justice flourished alongside the pursuit of poetry, learning, etiquette, rituals, and sacred music.

Under the auspices of the Yongle Emperor (r. 1404-1424), Admiral Zheng He (1371-1433) embarked on seven voyages to the ‘West Oceans,’ reaching as far as the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa; unlike the naval ventures of European powers, the Ming's maritime expeditions were dedicated to nurturing amicable ties and trade, eschewing colonial domination and military subjugation.

Evidence of tolerance emerged through the eventual formal acknowledgment of the legitimacy of Yangmingism, a bottom-up intellectual movement that underscored individual conscience and the universal call to sagehood, despite the prevailing state-endorsed Daoxue ideology. The Ming witnessed significant scientific advancements in various fields, with esteemed figures like Supreme Patriarch Sage Paul Siu (Xu Guangqi)(1562-1663) contributing to the progress of agricultural, astronomical, and technological knowledge. Advanced irrigation techniques, accurate calendars, and the publication of the Yongle Encyclopaedia, greatly enhanced East Asian wisdom.

In the ninth year of the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor (1627-1644), the chieftain of the barbaric Manchus usurped the title of ‘emperor,’ and invaded the East Realm twice in less than ten years, insulting King Injo (r. 1623-1649) of Joseon at Namhansan, and in the aftermath, so savagely murdered the Yongli Emperor (r. 1647-1662) in 1662, terminating the Ming lineage altogether. As the saying goes, after the downfall of the Realm of Great Illumination, Hwaha was no more.

Recall that, verily, the Manchu miscreants not only seized the very heart of civilisation but also decreed degrading mandates to shear the foreheads of men and don repulsive pigtails at the nape of their necks, along with the nomadic Manchu attire throughout their newfound colony.

This led to the retrogression of the civilised into the uncivilised, precipitated by prolonged years of incessant conflict, recurrent ethnic cleansings, the rampant persecution of the literati for ‘speech crimes,’ stifling the nascent roots of capitalism and the enlightenment of the common folk under the liberating teachings of Sage Wang Yangming (1472-1529) and his disciples most notably, enduring no less than two centuries of arrogant supremacy, and the enforced imposition of savage edicts.

‘Following the barbarians’ conquest of Hwaha, lamented King Jeongjo (r. 1776-1800) of Joseon, ‘the foul smell of blood has contaminated the seas, and the morals of attire and etiquette of Hwaha had evaporated in a territory of beasts.’

MING CULTURAL ACHIEVEMENTS

The Ming Empire, spanning from 1368 to 1662, cast a luminous influence upon the cultural tapestry of its devoted ally, the Kingdom of Joseon (1392-1897). A bond forged in the crucible of time, their union birthed a harmonious symphony of tradition and innovation, a legacy that resonates through the corridors of time.

At the heart of this illustrious Empire lay the Yongle Encyclopedia, a monumental testament to the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom. Commissioned by the Yongle Emperor (r. 1402-1424) in 1403, this magnum opus, comprising 22,937 manuscript rolls in 11,095 volumes, stood as a beacon of enlightenment, illuminating the minds of scholars and sages alike with its vast repository of wisdom spanning the realms of agriculture to technology. Within its hallowed pages, the secrets of the universe unfolded, ushering in a new era of intellectual enlightenment and scholarly pursuit.

Yet, the Empire's legacy extended far beyond the realms of academia, reaching into the very fabric of daily life. Through the alchemy of innovation, the Ming Empire revolutionised the art of printing, unleashing a torrent of knowledge upon the world. Woodblock colour printing, paper production, and the art of two-colour printing emerged as the heralds of a new age, transforming the dissemination of information and ushering in a renaissance of learning and discovery.

The Ming was a time of significant cultural advancement. The global community marveled at the blue-and-white porcelain crafted in imperial kilns, exalting the word ‘Ming’ as a symbol of exquisite ceramics. This period saw a surge in literacy among both sexes, nurturing a diverse literary landscape encompassing science, technology, and the arts. Esteemed literary works like The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West, Water Margin, and The Plum in the Golden Vase highlighted the era’s commitment to literary and artistic freedom.

In the realm of personal hygiene, the Ming's ingenuity shone brightly with the invention of the bristle toothbrush by the illustrious Hongzhi Emperor (r. 1487-1505) in 1498. A testament to the empire's commitment to health and wellness, this invention marked a significant leap forward in personal care practices, setting a new standard for cleanliness and hygiene across the land.

Furthermore, the Ming Empire's spirit of innovation reached even the vast expanse of the high seas, where the invention of ship rudders revolutionised maritime navigation. Guided by the stars and propelled by the winds of change, these technological marvels propelled the Ming's ships across the oceans, forging new trade routes and connecting distant lands in a tapestry of cultural exchange and mutual prosperity.

A SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP

Yongle the Great

영락대제 (r. 1402-1424)

Sejong the Great

세종대제 (r. 1418-1450)

The friendship between Emperor Yongle the Great of the Ming Empire and King Sejong the Great (posthunously honoured by the Myeong Commonwealth as 'Emperor Sejong the Great') of the Kingdom of Joseon, whose reigns overlapped for six years, was a shining example of significant diplomatic and cultural exchange between the two neighbouring realms during the 15th century.

The Yongle Emperor, the third monarch of the Ming, whose reign spanned from 1402 to 1424, was known for his ambitious architectural projects, compilation of the 11,095-volumed Yongle Encyclopedia which covered ancient wisdom on everything from morals to technology, dispatching of six massive peaceful naval expeditions to South Asia and East Africa, and extensive military campaigns against the remnants of the Mongol Empire. He sought to establish a strong relationship with Joseon, recognising its strategic importance and cultural contributions. King Sejong, the fourth ruler of Joseon, sat on the Throne from 1418 to 1450. He is renowned for his achievements in governance, science, and culture, particularly the creation of the Joseon script, Hangul.

The friendship between the two monarchs was characterised by mutual respect and admiration. They exchanged diplomatic envoys. Yongle and Sejong regularly shared their thoughts and literary works on topics ranging from history and philosophy to science and technology. This exchange of ideas and knowledge helped foster cultural and intellectual growth in both countries. In September 1424, when Yongle the Great died, Sejong the Great remained in mourning dress for 27 days, despite the rule set by the Hongmu Emperor (홍무제) (r. 1368-1398), founder of the Ming Empire and father of Yeongnak, that subjects should remain in mourning dress no more than three days after an emperor's death.

During the years 1592 to 1598, the 'Imjin Wars' marked two significant Japanese invasions of Joseon Korea. Initiated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the infamous Japanese warlord, these campaigns aimed to realise his longstanding ambition of advancing into the Ming Empire via the Korean peninsula. Despite an auspicious beginning with the capture of key cities like Pyongyang and Seoul, the first invasion encountered formidable resistance from a coalition comprising the Joseon navy under Admiral Yi Sun-sin, a substantial Ming land army, and local insurgents. This collective effort thwarted the Japanese advance, leading to a stalemate in 1593. Following fruitless peace negotiations, Hideyoshi launched a second, less successful invasion in 1597 before his demise the following year prompted the Japanese forces to retreat from the Peninsula. Reverberating as one of the largest military endeavors in pre-20th century East Asia, the conflict left a trail of devastation and irreparably strained relations between Japan and Korea.

The Wanli Emperor of Ming played a crucial role in supporting Joseon against the Japanese invasions led by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The Emperor dispatched a large land army to aid the Koreans in repelling the Japanese forces. The Ming forces fought alongside their Joseon allies, and contributed significantly to the eventual stalling of the first Japanese invasion in 1593.

The Kingdom of Joseon expressed its gratitude to the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572-1620) for his support during the Imjin Wars. The government and people of Joseon acknowledged the crucial role Ming troops played in helping defend their country against the Japanese aggression. The assistance the Wanli Emperor and the mighty Ming armed forces provided was instrumental in turning the tide of the war and preventing further Japanese advances into Korea.

The Wanli Emperor's support and the Ming army's contributions in the Imjin Wars were deeply appreciated by the Joseon leadership and population, and remembered with gratitude for Ming's crucial role in defending its ally faithfully during this tumultuous period in East Asian history.

A LIFESTYLE OF RITUAL PROPRIETY

In a world of moral collapse and the return of barbarianism everywhere, the Myeong Commonwealth is undoubtedly one of the last bastions of human civilisation: it is undoubtedly, the Realm of Humaneness and Righteousness (인의지방), the Realm of Propriety and Etiquette (예의지방), and the Realm of Noble Character (군자지국). Myeongeans are committed to leading lives that revolve around a set of rites known as lye (례), whose purpose is to cultivate the moral characters of individuals in accordance with Divine Reason (천리).

Lye encompasses a wide range of practices, including ceremonies, festivals, and rites of passage such as weddings and funerals. It also includes everyday activities such as greeting others, table manners, and dress codes. The rule of ritual propriety emphasises the importance of performing these practices with sincerity, respect, and adherence to tradition. By doing so, individuals show appropriate respect for their ancestors, their elders, and the natural world, all of which are seen as essential components of a harmonious society. As the premier Confucian micronation that the world has never seen before, the Myeong Commonwealth celebrates Five Rites (오례) that were mentioned in the ancient Confucian classic of the Rites of Ju (《주례》):

Auspicious Rites (길례): These rites are performed to celebrate good fortune. They are often conducted during important life events such as weddings (pictured below), the birth of a child, or the opening of a new business. Auspicious rites typically involve rituals, prayers, and offerings to God to show reverence, and to ancestors to demonstrate that death cannot stop filial piety from being paid (pictured above).

Inauspicious Rites (흉례): In contrast to auspicious rites, inauspicious rites are performed to ward off or mitigate negative energy or harm. They are often practiced during times of illness, accidents, or funerals. Inauspicious rites may include rituals such as cleansing, purification, or offerings to appease spirits and protect against misfortune.

Congratulatory Rites (가례): Congratulatory rites are performed to celebrate achievements or special occasions such as graduations or promotions. They are usually conducted to express congratulations and to wish the person good luck in their future endeavors.

Hosting Rites (빈례): Hosting rites are conducted when welcoming guests or visitors. They involve observing proper etiquette, offering hospitality, and ensuring that guests feel respected and well-cared for. Hosting rites may include rituals such as serving tea, offering food, and providing comfortable accommodations.

Military Rites (군례): Military rites are performed in the context of warfare or military activities. They involve rituals and ceremonies to boost morale, honor fallen soldiers, and seek protection from deities or ancestral spirits. Military rites often include offerings and prayers for victory, strength, and the well-being of soldiers.

These rites together reflect the importance placed on maintaining harmony, promoting auspiciousness, and showing respect for various aspects of life in Confucian culture. In accordance with the Rites of Ju, the Lord Patriarch (the second-highest ranking prelate of the Supreme Confucian Congregation) is the primary authority responsible for the standardisation of these rites.

MYEONGBOK

Proper attire (정의관) is crucial for Confucianism, which strongly emphasises showing respect and modesty towards others by dressing appropriately and modestly in different social contexts. Proper attire helps to signify one's social status and role, allowing for clear distinctions and a harmonious social structure, and is considered a part of the ritualistic aspect of Confucian practices, representing adherence to traditional values and cultural norms. Confucianism emphasises self-cultivation and personal development. Wearing proper attire is seen as a way to cultivate self-discipline and self-respect, as it reflects one's commitment to upholding social norms and presenting oneself in a dignified manner.

The Ming Empire had a significant influence on Joseon's fashion and attire. The exchange of ideas, trade, and diplomatic relations between the realms facilitated the transmission of clothing styles and trends. One of the most significant impacts of Ming attire on Joseon attire was the introduction of Ming-style court dress. The Ming Empire placed great importance on court protocol and etiquette, and the attire worn by officials and nobility reflected this. Ming court dress was characterised by long robes with wide sleeves and a mandarin collar, often made of silk and decorated with intricate embroidery. This style was adopted by the Joseon court, particularly during formal ceremonies and events.

The Myeong Commonwealth developed its unique micronational attire: the Myeongbok (명복), which features a mix and match of the attire of the Ming Empire and the Daehan Empire. HM The Emperor and other members of the Imperial Household; HS The Supreme Patriarch and Colinals of the Supreme Confucian Congregation; and peers of the Commonwealth regularly wear Myeongbok in ordinary meetings and events; other members of the Myeong Commonwealth from all walks of life often wear Myeongbok on public holidays and family occasions.

Ming attire also influenced Joseon everyday wear. Ming-style jackets and trousers became popular among the Joseon upper class, and women's clothing began to feature wider sleeves and longer skirts. Additionally, the use of silk as a material for clothing became more widespread in Joseon, reflecting the influence of Ming fashion. Against this background, the Kingdom of Joseon evolved the Hanbok (한복), which is characterised by simpler lines, vibrant colors, and natural fabrics like cotton and hemp (pictured above). Unlike Myeongeans, Koreans no longer wear the Hanbok on a daily basis but only on special occasions.

MYEONG ARCHERY

Myeongeans favour archery (사) as a sport that goes beyond the physical act of shooting a bow and arrow. It is a means of developing important qualities such as discipline, focus, and self-control, which are essential for individuals of exemplary character. Ancient sages used archery as a metaphor to teach the Way of Humaneness.

According to Sage Confucius, the competition of the man of exemplary character involves ascending to one's position in an archery match with deference and drinking from the ritual cup upon descending. Sage Mencius likened the person who seeks to be humane to an archer who adjusts himself before shooting and takes responsibility for his failure rather than complaining about those who outperform him.

Together with rituals (예), music (악), charioteering (어), calligraphy (서), and mathematics (수), archery is one of the well-established Six Arts (육예) of the Confucian tradition. The Six Arts aim to cultivate a well-rounded individual who can contribute meaningfully to society. Each art represents a different aspect of personal development. Archery reminds monarchs and officials of their duty to defend their people and the Commonwealth against all threats. As a Confucian micronation, the Myeong Commonwealth proudly practices archery as a sport that reflects its cultural heritage and micronational pride.

MYEONG GO